How & Why “Paul Is Dead” Went Viral

EXCERPT From Chapter Seven • The Last Leg • Turn Me On, Dead Man • Days after Abbey Road’s release, during Moratorium week, there was unexpected Beatle news:

I was in History class and one of the jocks said he heard Paul was dead. The teacher discussed it with us for a while. Some people knew about it and knew some of the clues. The jock probably just said it to be cool; he wasn’t that into the Beatles. Male, b. ‘55

With passion, velocity, and density of Beatletalk not witnessed since the band’s arrival five and a half years earlier, a rumor that Paul died in 1966 spread through neighborhoods and schools. A male fan, age eighteen at the time, recalls, “We just got swept away with it. There was a crazy frenzy about it, the way it spread.”

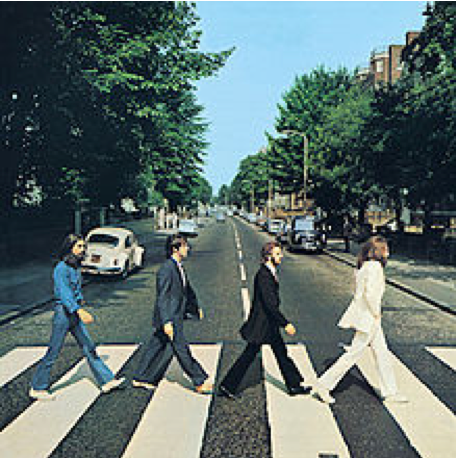

According to the rumor, Paul had been replaced by a look-alike after dying in a car crash, events which the band painstakingly and successfully hid from the public. However, it was revealed that clues about the accident and proof Paul was dead could be found in songs and on album covers, as far back as Yesterday and Today. Many of the clues were on Abbey Road, one of the most prominent being, ironically, the license plate on the VW Beetle that would not have been there if the band had their way.

Paul Is Dead fever went on for more than two months. Fans from ten to twenty-five, in elementary school and in graduate school, looked at albums with magnifying glasses, identified symbols, and listened to songs, sometimes backward, for clues. And like early Beatleing, hunting for Paul Is Dead clues was a group activity and gave fans much to explore and discuss.

I was at a friend’s house, and her friend’s older brothers and sisters were talking about the rumor that Paul was dead and playing the records backwards. They were having lunch; grilled cheese and chicken soup. Female, b. ‘61

There was a Halloween party where someone put Paul in a coffin. We looked for the clues and talked about it. Male, b. ‘54

I was in college at the time. We played some songs backwards. We followed the clues. We didn’t think he was dead, but it was fun. Female, b. ‘47

A Beatle spokesman called the rumor “a load of rubbish” but that didn’t quell the frenzy. Several thought the band did it as a “joke at fans’ expense because they knew people combed for deeper meaning.” A female fan, age fourteen at the time, recalls, “I always thought the Beatles were behind it, that it was a publicity stunt. That disappointed me. I lost some of my trust in them. But we looked for the clues.”

Very few thought the Beatles were behind the rumor, and not all who thought so felt disappointed. A male fan, also fourteen at the time, recalls, “I think it was a marketing ploy to sell records, and I still do. These things are there. I didn’t think he was dead but I think they did it on purpose. John’s a practical joker, they all were.” A female fan, age thirteen at the time, said, “The Beatles had a mysterious side and knew how to put in cool stuff that kids would appreciate.”

Looking for clues meant going back to earlier albums that many younger fans thought were “for big kids.” Now these ten and eleven year olds wanted their own copy of Sgt. Pepper. The Beatles weren’t behind the rumor but it certainly sold records. It also sold special-issue magazines dedicated to the rumor. A New York City radio station broadcast an hour-long discussion about it, and the early morning AM signal was heard in thirty-eight states.

Rolling Stone ran an article called “One and One and One is Three?” in late October, explaining how the rumor got started and discussing some of the clues.[26] The New York Times ran its second article on the persistent rumor in early November, this one titled “No, No, No, Paul McCartney Is Not Dead.” For the most part, fans didn’t believe Paul was dead, but they still “looked for clues and played songs backwards.”

At the height of the frenzy, a Life magazine reporter showed up unannounced and unwelcome at Paul’s farm, and after a testy interaction—photos of which were destroyed by gentlemen’s agreement—was able to get a rare, extemporaneous interview with McCartney, who conjectured that the rumor started because he hadn’t “been much in the press lately.” He said he’d done “enough press for a lifetime” and that he’d rather be “a little less famous these days.” Paul continued, dropping a bombshell that got less attention than Life’s black and white photo spread proving he was alive:

I would rather do what I began by doing, which is making music. We make good music and we want to go on making good music. But the Beatle thing is over. It has been exploded, partly by what we have

done, and partly by other people. We are individuals—all different. John married Yoko, I married Linda. We didn’t marry the same girl.

By late November, when a New York City television station broadcast a mock trial on the rumor, featuring famed attorney F. Lee Bailey, the rumor had run its course, but fans didn’t stop looking for clues, and still haven’t. The rumor was started by a college student and a DJ, but the hundreds of clues that eventually emerged were created and shared by fans, who collectively developed a game that allowed for focused Beatleing.

Since the beginning, countless hours had been spent listening and studying album covers—this was simply more of the same. Those with good imaginations created meaning out of ambiguous detail to fit an absurd, emotionally charged narrative. Also, it’s more appealing to believe the Beatles had the cleverness and forethought to create these clues, in benignly conspiratorial fashion, than to believe they were created collectively by fellow fans. That the rumor completely defies logic and common sense was irrelevant to the function it served.

When the rumor started, fans had been seeing a lot of John but not much of Paul, George, or Ringo. And they’d seen a lot of John side projects that were moving, irretrievably, in non-Beatle directions. They were reading about delayed projects, disagreements, and financial wrangling. And then there was the new album—a tidy showcase with a feel of grand finality that explored, especially on “Side Two,” themes of maturity, disappointment, and unknown futures while offering aphorisms for the ages. Like any compulsive behavior, looking for and talking about Paul Is Dead clues assuaged anxiety—not about whether Paul was dead, but about whether the Beatles were still alive.

Unbeknownst to fans, John told the band he “wanted a divorce” in September but agreed to keep it quiet until some pending business issues were resolved. Paul, who most loved being a Beatle and who most defined himself in that way, was angry and depressed, going through his own cold turkey. His casual remark to the Life reporter had been true for months, but most fans, listening to a new album, rediscovering old ones, and expecting another long-delayed release early in the new year, were too distracted to notice.